Comments

- No comments found

Claudia Goldin’s Nobel prize lecture, “An Evolving Economic Force,” has now been published in the June 2024 issue of the American Economic Review.

Or if you prefer, you can watch the watch the lecture (with more numerous slides!) from the link at the Nobel website. She writes:

Women are now at the center of the world’s economies. Employment rates for women are at historic highs across the globe. Of the 165 nations … almost 60 percent have female employment rates (for those 25 to 54 years old) that exceed 0.70, and 80 percent exceed 0.50. For comparison, in the United States one-half of the women in that age group worked in 1970 and around three-quarters have done so ever since the early 1990s. … Women are at the center of the world’s economies not just because they are engaged in paid employment to a significant degree. They are rapidly becoming the better-educated gender, constituting the majority of college students in every one of the 38 OECD nations. Women do the vast amount of care-work across the world. And they largely determine the birth rate.

Regular readers of this blog will recognize these themes from earlier posts that have discussed Goldin’s work. For example, there is the well-known pattern that women’s work in the paid labor force first diminishes with economic growth, and then expands. This figure, taken from the Nobel lecture, shows the pattern of married US women who worked outside the home over time:

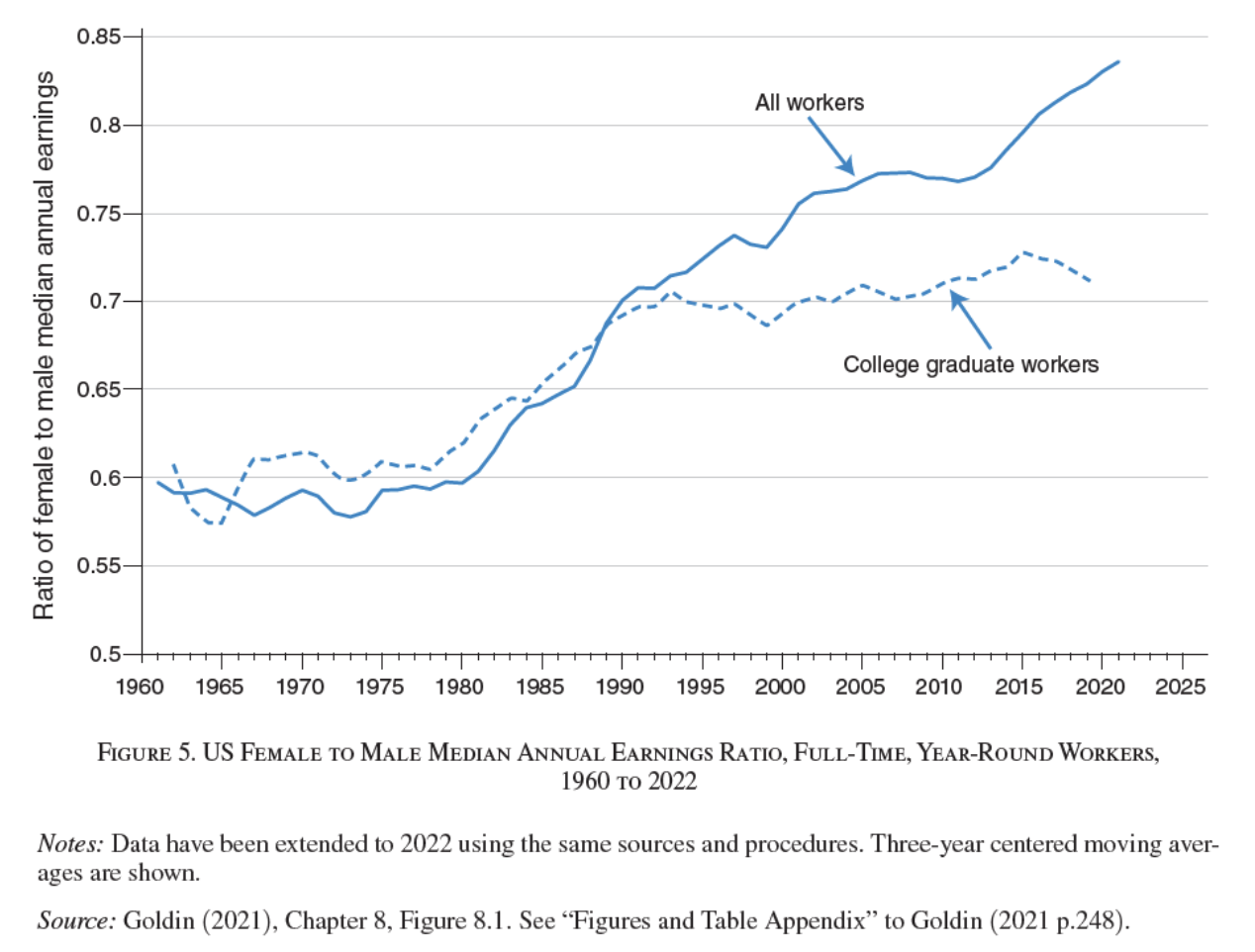

But here, I want to focus on a more recent pattern: the pay gap between men and women over the last 60 years or so. As the figure shows, the ratio of female-to-male earnings doesn’t move much from 1960 to 1980. At that point, there is a rapid rise in the ration, although not up to 1. Also, the earnings ratio for college-educated women levels off around 1995. So what is going on here?

The common economic story about the lack of change in the ratio during the 1960s and 1970s was that this was a time when entry of women into the paid labor force was especially high. Many of these women were older and lacked substantial paid work experience. Thus, the labor market entry of this group tended to hold down wages for women. As Goldin writes about this period:

The persistence of the gender gap in earnings was, in large part, due to the increase in women’s labor market participation, not despite it. As participation rates increased, women, whose job experiences were somewhat distant and brief, were pulled into the labor force. That put downward pressure on the earnings of the average working woman relative to the average working man. The stability of the gender gap in earnings given the increase in female labor force rates was a source of great frustration to those in the resurgent US women’s movement in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Banners at rallies decried the fact that women were working more, yet not being paid more relative to men. Most who interpreted the aggregate statistics as revealing a discriminatory process did not realize that the average job experience of working women was being depressed by the entry of less experienced and generally older women.

But by around 1980, this earlier process had run its course. A larger share women in the labor market had higher levels of education and paid job experience, and the wage ratio begins rising.

The current question is what explains the remaining wage gap–and in particular, the higher wage gap for college-educated women? As Goldin poses the question: “The question is particularly puzzling because today, many of the determinants of earnings are nearly the same between men and women and some, in fact, favor women. If earnings in competitive labor markets are determined by pre- labor market characteristics (such as education and training) as well as those pre-job (such as experience in previous positions), and if these characteristics have become nearly identical by sex and some favor women, what remains?”

Goldin brings some additional evidence to bear on this question. One fact is that the average ratio of female-to-male earning declines with age: “Earnings of women relative to those of men begin closer to parity (almost at 0.95 for the youngest age group in the most recent birth cohort), but that ratio decreases with age and thus with a host of other life cycle transitions. By their late thirties, the ratio for the most recent cohort shown is 0.8. The widening of the gender earnings ratio by years since college or professional school graduation is even steeper among higher income occupations, such as those in the corporate and financial sectors …

A substantial reason for the decline is that having children is for women associated with a substantial decline in hours worked and earnings. Goldin writes: “[T]he weight of the evidence is that the earnings of women plummet with the event of a birth and do not recover. Furthermore, most of the change comes from a reduction in hours of work or in participation, rather than from a reduction in earnings per hour, although that factor contributes somewhat.”

A final fact-based clue is that the difference in the female-to-male earnings ratio is more related to differences within occupations, rather than to men and women ending up in different occupations: “It is important to realize that the majority of earnings differences by occupation are within rather than across occupations (given around 500 occupations and a sufficiently large dataset).”

The last few decades in the US economy have been a time of growing inequality of incomes at the very top of the distribution. These jobs at the very top of the income distribution often involve extraordinary commitments of time, and the people holding these jobs not only work more hours, but their total salaries represent a much higher hourly wage rate, as well. To put it another way, there is a “part-time earnings penalty,” in which those who work part-time not only have fewer hours, but also earn less per hour. As an example, consider a man and woman who attend the same law school and perform equally well. For a few years, they earn very similar pay. But when the woman has children, her hours drop substantially, and she is no longer on the track to be one of the heavy-hour and top-paid partners.

The part-time earnings penalty does not apply across all jobs. Goldin writes:

How can the gender earnings gap be reduced? One part of a solution is to lower the cost of flexibility. The simplest way is to create virtual substitutes between workers. That has been done in various occupations that use IT to effectively pass information and hand off clients. Teams of substitutes could be created, as they have been in pediatrics, anesthesiology, veterinary medicine, personal banking, many tech jobs, primary care medicine, and pharmacy.

The case of pharmacy is instructive. The occupation of pharmacist in the United States today has almost no part time earnings penalty and the earnings gap between male and female pharmacists is small. But that was not always the case. In the 1970s a substantial fraction of male pharmacists owned a pharmacy and many hired female pharmacists. The gender earnings gap was substantial. Several changes occurred in pharmacy that greatly narrowed the gender gap in pay but that had nothing to do with gender issues. Technological changes enhanced substitutability among pharmacists, pharmacy employment in retail chains and hospitals increased, and independent pharmacies declined (Goldin and Katz 2016). Change in other occupations, such as pediatrics, did emanate from the demands of professionals who wanted to spend more time with their own children and formed group practices that facilitated substitutability.

The remaining female-to-male earnings gap, at least in the United States, seems linked to this mixture of motherhood penalty and part-time earnings penalty. Changing the motherhood penalty involves redesigning family interactions, which seems hard, while changing the part-time earnings penalty seems perhaps tricky, but also do-able.

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest