Comments

- No comments found

Through the Trump and Biden administrations, it has been a policy goal to reduce imports from the US to China.

While US imports from China have declined, EU imports from China have been on the rise. Mary E. Lovely and Jing Yan tell the story in “While the US and China decouple, the EU and China deepen trade dependencies”.

A common way to measure the concentration of a market, whether looking at the extent of market competition in a US industry or the extent of concentration in foreign trade, is called the Herfindahl-Hirshman index . The arithmetic is simple: divide the market into shares, square the shares, and add them up. For example, say that an industry has four firms that each have 20% of the market, and then 20 firms that each have 1% of the market. Then the HHI would be 4(202) + 20 (12) = 1620. You can do a similar calculation for a countries’ reliance on imports: that is, look at the share of imports a country is receiving from each of its trading partners, square the shares, and add them up.

(The uninitiated may wonder why the market shares should be squared. Why not, say, just add up the market share of the four biggest or the ten biggest firms? Indeed, sometimes you do see measures of the “four-firm” or “10-firm” concentration ratio calculated in this way. In say that you are comparing two industries. In both of them, the four-firm concentration ratio is 80. However, in one industry the four largest firms each have 20% of sales; in the other industry, the largest firm has 77% of sales and the next three firms each have 1%. The four-firm ratio is the same, but obviously, the second industry is much more concentrated. Squaring the shares puts additional importance on the biggest firms when measuring concentration.)

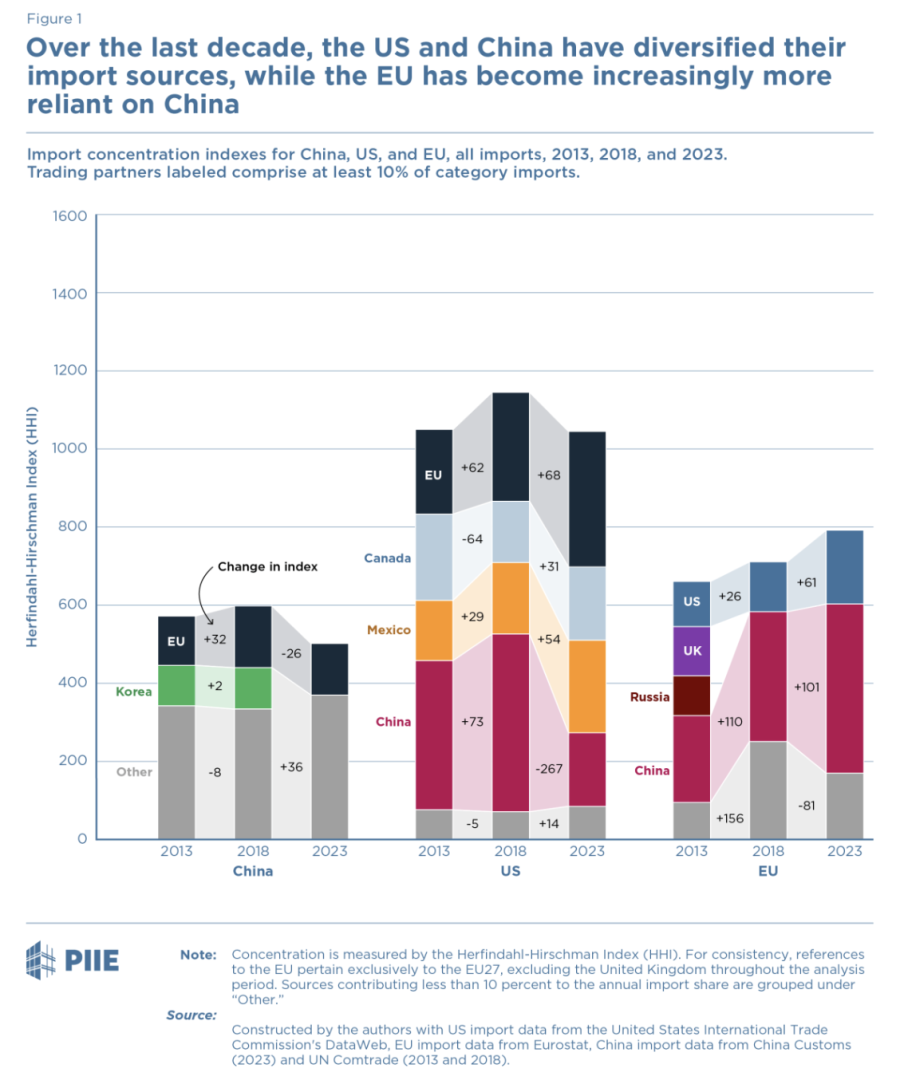

When Lovely and Yan do this calculation for the US, the EU, and China, comparing 2013, 2018, and 2023, they find:

China’s import sourcing is the most diverse of the three big regions; its concentration index is substantially lower than those of the other two, figure 1 shows. Only the European Union provides more than 10 percent of the total value of China’s imports. The European Union also relies on a diverse set of suppliers; just two sources—the United States and China—provide 10 percent or more of the European Union’s import value in 2023. Focusing on changes over time, figure 1 also shows that both China and the United States reduced their sourcing concentration between 2018 and 2023, a reversal after the growth between 2013 and 2018. In contrast, Europe’s concentration rose across the full 10-year period.

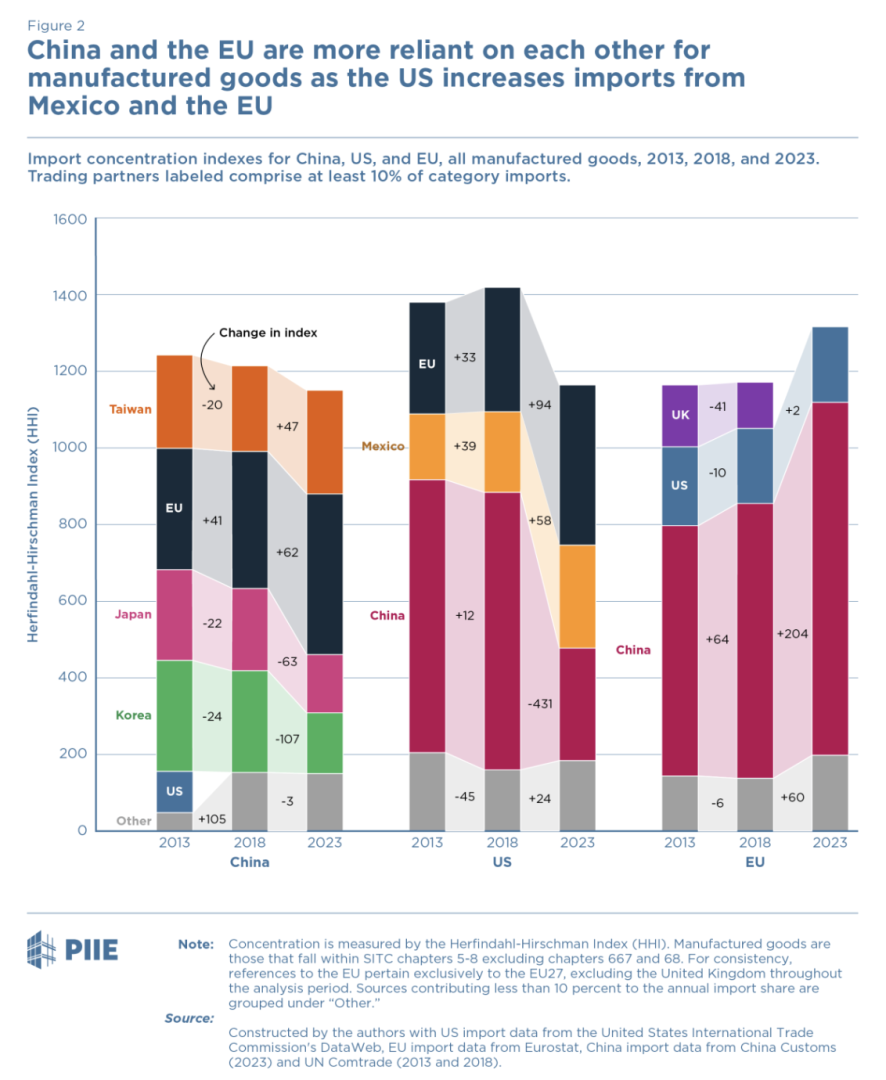

The authors find a loosely similar pattern when they focus only on imports of manufactured goods. That is, the US is less reliant on manufactured imports from China, but the share of imports from the EU, Mexico, and other countries has risen. China has seen a greater share of its manufactured imports from the US and from Taiwan, but a drop from others. In the EU, the share of manufactured imports from China is up substantially.

In short, these patterns seem to suggest that imports not coming from China to the US economy are, in a substantial way, ending up in the EU economy instead. This pattern suggest that if the goal of US trade policy is to reduce China’s footprint in the global economy, it is unlikely to do so. Indeed, given that imports often pass through the production process in several countries on their way to a final product, it’s plausible that some Chinese exports are going to Mexico and the EU, being incorporated into other products, and then ending up as US imports.

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest