Comments

- No comments found

Over the past decade, multinational corporations have employed increasingly complex tax evasion strategies to minimize their tax liabilities, often costing governments billions in lost revenue.

One of the most infamous strategies was the "Double Irish Dutch Sandwich," a tax loophole that allowed corporations to shift profits through various subsidiaries to avoid paying taxes in the U.S. and Ireland. However, recent reforms in international tax laws have curbed the effectiveness of this scheme. As changes in tax regulations continue to evolve, the underlying issue persists: the diversion of talent and resources away from innovation and productivity into the endless pursuit of tax avoidance.

I wrote a decade ago about the Double Irish Dutch Sandwich, a strategy for corporations to evade taxes that was widespread and large-scale enough to come to the attention of the International Monetary Fund. But due to various changes in national and international tax agreements, the strategy seems to have faded substantially. Ana Maria Santacreu and Samuel Moore of the St. Louis Fed provides some background in “Unpacking Discrepancies in American and Irish Royalty Reporting” (August 08, 2024).

For those who don’t keep up to speed on the details of international tax evasion schemes, Santacreu and Moore describe the Double Irish Dutch Sandwich works like this:

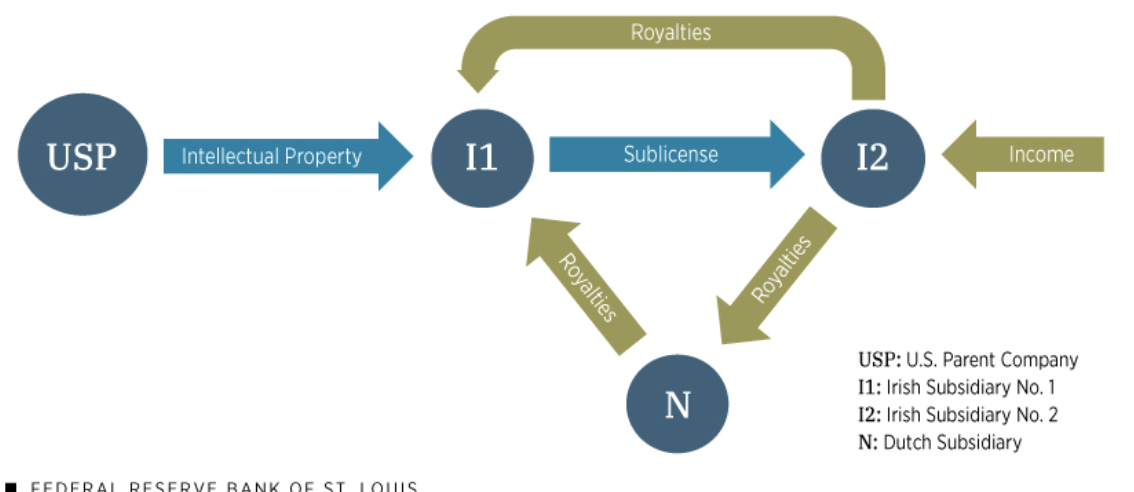

The Double Irish with a Dutch Sandwich tax scheme, as illustrated in the third figure, involved a complex arrangement between a U.S. parent company (USP) and three foreign subsidiaries. The first Irish subsidiary (I1) was incorporated in Ireland but managed from Bermuda, allowing it to avoid both Irish and U.S. taxes. The second Irish subsidiary (I2) was incorporated and managed in Ireland. The purpose of I2 is to control foreign distribution and collect income. A Dutch subsidiary (N) acted as an intermediary between I2 and I1 to avoid Irish taxes.

The scheme worked by exploiting specific provisions in Irish and U.S. tax laws. A USP would transfer intellectual property ownership to I1. Then, I2 would sublicense the intellectual property from I1 and pay royalties. These royalties would flow from I2 to N, and then from N to I1, taking advantage of European Union tax regulations. This structure allowed profits to be shifted to tax havens like Bermuda, effectively minimizing tax liabilities for the entire corporate structure.

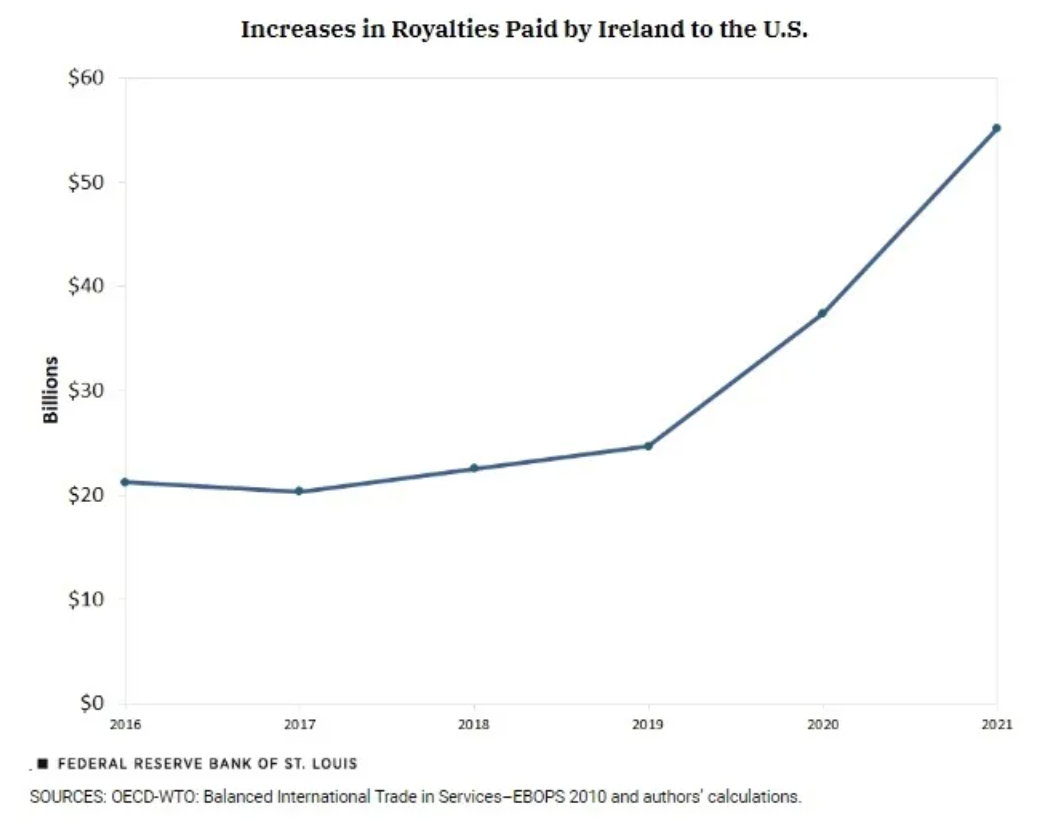

However, a combination of Irish tax reforms in 2015 and changes in the US Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 made this strategy ineffective: “Consequently, Irish companies began paying royalties directly to American parent companies instead of routing them through tax havens.”

The shifts in royalty payments tell the story. This figure shows royalty payments by Irish companies to the US, which doubled from 2019 to 2021.

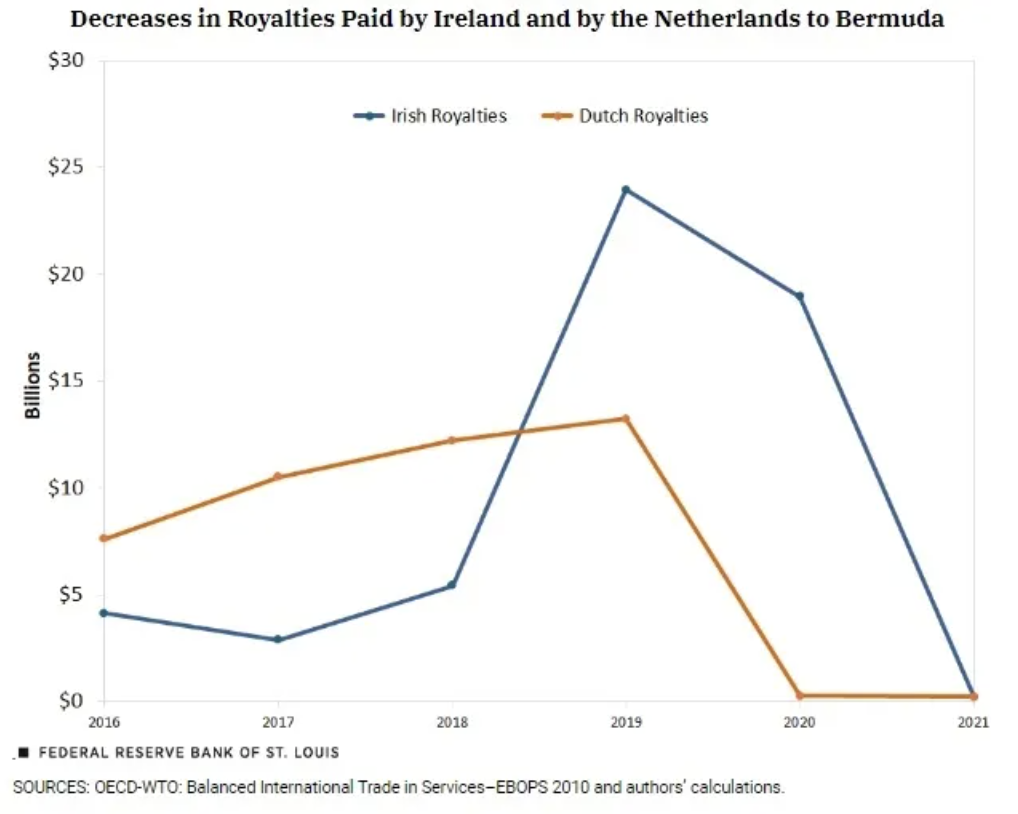

Conversely, tax payments from Ireland and from the Netherlands to Bermuda, well-known for its near-zero corporate taxes, went way down–showing a decline in corporate profits being routed through Bermuda.

I’m sure the international tax lawyers around the world are strategizing new tax evasion strategies even as I write these words. But it’s worth remembering that there are two large costs at play here. The obvious loss is to government revenue, but the more subtle and still very real loss is the diversion of high-powered talent from what could have been gains in efficiency and productivity to focus instead on corporate reorganizations and tax evasion games.

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest