Comments

- No comments found

Thinking back over the half-century or so that I have been paying attention to the US economy, I can’t offhand remember a time when most people believed that the quality of American jobs was high and/or rising.

Here’s how Adam Ozimek, John Lettieri, and Benjamin Glasner describe the common complaints in their report, “The American Worker: Toward a New Consensus” (Economic Innovation Institute, June 2024).

Consider a common narrative one hears about todayʼs economy. It goes something like this: Workers are experiencing an age of unprecedented disruption. The rise of e-commerce and automation, increasing foreign competition, and the proliferation of gig platforms have upended the typical employer-employee relationship and the stability that workers used to enjoy. As a result, more workers are taking on side gigs or cobbling together multiple part-time jobs just to get by. Not only that, but even good jobs are more precarious than in previous eras. Back when manufacturing ruled the U.S. economy, workers could expect a job for life. Today, they are forced to switch jobs more often than ever before.

However, when Ozimek, Lettieri, and Glasner then consider the actual statistical evidence behind these fears, often with comparisons back to 1980 or the 1990s, they don't provide evidence in support. For example, they write:

Not only has it long been uncommon for workers to hold more than one job at once, Americans today are even less likely to have multiple jobs than they were in the past. Multiple jobholders have trended down from 5.9 percent of workers in 1994 to just 5.0 percent today. … If not through multiple jobs, perhaps workers are responding to increased disruption or precarity by working longer hours? Just the opposite. In the early 1960s, production and nonsupervisory employees—workers who do not manage other workers—averaged close to a 40-hour workweek. By 1980, that had fallen to just over 35 hours per week. Today, itʼs under 34 hours per week—close to a historical low during non-recessionary periods.

What about part-time work? Are Americans being forced to settle for part-time jobs when they would rather have the security of full-time employment? Here again, the answer is clearly no. In total, roughly 19.3 percent of the labor force works part-time, lower than in 1980. Only 2.6 percent of the labor force does so out of economic necessity—close to a historical low. The vast majority of those who work part-time do so by choice and the vast majority of those who want full-time work can find it.

We also find zero evidence for the idea that workers are switching jobs more frequently than before. The share of workers changing jobs in a given year has fallen significantly, from 16.9 percent in 1980 to 11.1 percent today. Over the same period, the median length of time someone works for a given employer has gone up from 3.2 years to 4.1 years. In fact, there is good reason to believe that the low levels of job turnover are a cause for concern. Job switching tends to meaningfully boost a workerʼs lifetime earnings, and it also helps knowledge and productivity gains to spread throughout the economy.

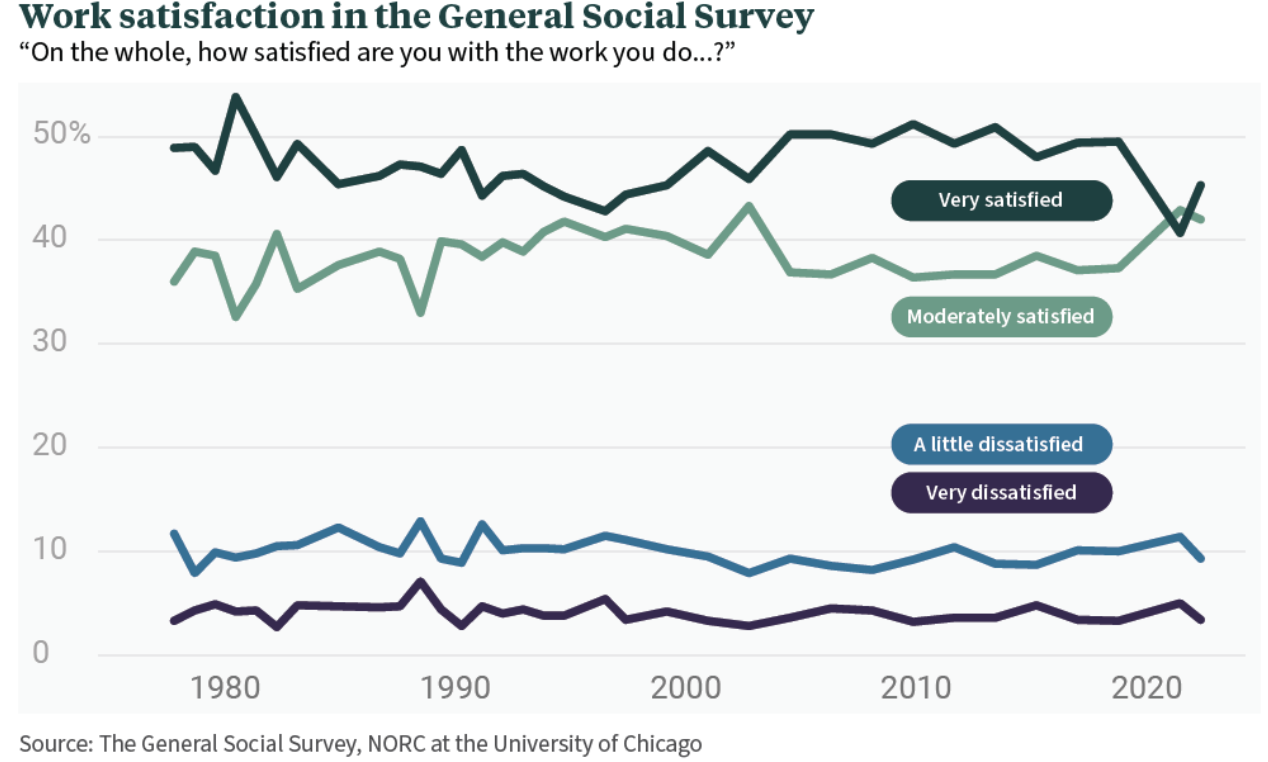

Their roll-call of evidence about how wages and work conditions are not in fact declining, but are better than a few decades ago, goes on and on. Here, let me mention what people actually say about their jobs in response to surveys. The General Social Survey has since 1972 been conducted by an opinion research center based at the University of Chicago, with funding from the National Science Foundation. When Americans are asked about their job satisfaction, here’s what they say:

Yes, there’s some fluctuation, like a drop in job satisfaction during the pandemic. But between 80-90% of Americans have been either “very” or “moderately” satisfied with their job going back to 1972.

That’s just one survey, right? Well, the Gallup poll does a job satisfaction survey, too, asking: “How satisfied or dissatisfied are you with your job? Would you say you are — completely satisfied, somewhat satisfied, somewhat dissatisfied or completely dissatisfied with your job?” In 2023, the answer was 50% completely satisfied and 41% somewhat satisfied. The highest level of satisfaction was down a bit from the pre-pandemic answers of 2020, when 56% reported being completely satisfied and 33% were somewhat satisfied.

That’s just two surveys, right? Well, the Conference Board also does a survey of job satisfaction: “The Conference Boardʼs multi-decade survey of U.S. workers recently found that job satisfaction has improved for thirteen consecutive years, resulting in the highest levels recorded since the surveyʼs inception in 1987.”

Sure, there are plenty of issues with the labor market and the economy as a whole. But as one example, concerns about high prices for housing, or health insurance, or a college degree, or inflation in general are not actually complaints about the jobs that people have. The desire for salaries and wages with higher buying power and jobs with better career prospects aren’t quite the same as hating your current job, either. There’s a kind of fake profundity that delights in solemnly announcing how the world is going to hell. Almost two centuries ago, John Stuart Mill was writing disapprovingly about how “the man who despairs when others hope… is admired as a sage”–as if pessimism was necessarily synonymous with hard-earned wisdom, rather just emotional dyspepsia.

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest